10. World Views & the Interpretation of Modern History (ii)

This week we will look at the ways four further world views generate very different approaches to understanding the "human story":

- Liberalism

- Postmodernism, redundancy

- a "Creedal" world view

- indigenous culture

Liberalism

(Latin

liber, which means "free").

Liberalism (also known as higher criticism, modernism, neo-orthodoxy, Bultmannism, or new hermeneutic) is a theological movement rooted in the early 19th century German Enlightenment, notably in the philosophy of Immanuel Kant and the religious views of Friedrich Schleiermacher. It is an attempt to incorporate modern thinking and developments, especially in the sciences, into the Christian faith. Liberalism emphasizes ethics over doctrine and experience over Scriptural authority. While essentially a 19th century movement, theological liberalism came to dominate many mainline churches in the 20th century.

The Sadducees were the liberals of Jesus day. They rejected the supernatural, including angels, spirits, resurrection, judgement, and divine intervention in the world. Jesus criticised them for "knowing neither the Scriptures nor the power of God" (Matthew 22:29

Liberals today believe that

- the Bible may, or may not, contain the Word of God, or words about God, however, it is a book, written by men, for men; its stories are folklore that should not be taken literally and can be adjusted to meet modern needs; it has no moral or spiritual authority

- statements in the Bible that are contrary to modern science may be ruled out

- Jesus was not divine (what is divine anyway?)

- notions of sin, judgement and atonement have been overtaken by ethics

Protestant liberal thought in its most common forms emphasizes the universal Fatherhood of God, the brotherhood of man, the infinite value of the human soul, the example of Jesus the man, and the establishment of the moral-ethical Kingdom of God on Earth.

Liberalism gave rise to other movements with varying emphases. Among these movements have been the Social Gospel, theological Feminism and Liberation theology. One product of these movements is the Myth of Christian Origins which likewise denies the divinity of Christ and the authority of the Bible.

Many modern ministers and churches have been influenced by liberal claims that evangelicalism is lacking in scholarship, unable to provide answers to secular humanism and new science.

Some differences between evangelical and liberal theologies

|

Evangelicals believe that...

| Liberals believe that...

|

|---|

|

There are absolutes, established by God; many things in the world are stable and fixed (Malachi 3:6a; Hebrews 13:8)

|

Theology must not go beyond tentative assumptions; there are no absolutes.

|

|

Conclusions can be reached in the field of theology that can be regarded as certain and final (John 14:6)

|

It is unsafe to develop fixed views about God and theological views. Who/what is God? Who/what is truth?

|

|

The Bible was written by men under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit; it is the infallible and inerrant Word of God (2 Peter 1:20-21).

|

The Bible "contains" (or may not) the Word of God or words about God; it is just a book, written by men, full of errors, subject to investigation. The Old Testament is about Jews, for Jews.

The Bible is unreliable; the Gospels are inaccurate, inconsistent.

"The Old Testament is Jewish literature. In it are to be found folklore, defective history, half savage morality, obsolete forms of worship based on primitive and erroneous ideals of the nature of God and crude science". (Bishop Ernest Barnes, 1 April 1874 - 29 November 1953, an English mathematician and scientist who later became a liberal theologian and Catholic bishop.)

|

|

Faith is the basic norm for the Christian life (Hebrews 11:6).

|

Any modern man or women who honestly faces all the recent scientific discoveries can no longer accept the supernatural elements of Christianity. "Faith" does not need any historical or objective support because it is existential.

|

|

Modern man must adjust to the Bible.

|

The Bible must adjust to modern man. The Bible is a human document, written to inspire religious experiences. We are free to interpret it as we wish and decide what we want to keep/exclude.

|

|

The answer to our problems is for man to be reconciled to God through Jesus Christ.

|

The answer to our problem is man's reconciliation with man.

|

|

All men are sinners.

|

Beliefs in doctrines such as original sin offend modern sensibilities.

|

|

Jesus Christ was both human and divine, the Son of God.

|

Jesus' divinity was invented by religious writers. The so-called miracles of the Bible should be seen as statements of belief, not literally; it has out-of-date stories, concepts and values.

|

| The death of Christ paid for the sins of the world.

|

Notions of sin and sacrifice are Greek/Jewish ideas that must be reinterpreted for modern times. We need to avoid "butcher shop religion".

|

Results of liberalism are: confusion re belief; selectivity (people take what they want and reject the rest); declining church attendance; naturalism; growth of cults; moral void and relativism ("No one can tell me what to believe in or how to live"); religion that has form but no power; irrelevancy (why bother with Christianity?) and death of hope.

"See to it that no one takes you captive through hollow and deceptive philosophy, which depends on human tradition and the elemental spiritual forces of this world rather than on Christ. For in Christ all the fullness of the Deity lives in bodily form, and in Christ you have been brought to fullness. (Colossians 2:8-10)

Postmodernism, Ctd.

The period of "modernism", which was strong from the days of the Enlightenment until well into the 20th century, is sometimes termed the "Age of Reason". However, with all its hope for advancements in morality, learning, science, political understanding and global unity modernism failed to deliver results in the eyes of the "postmodern". (Witness a 20th century with more blood shed through wars than any other in human history.)

Postmodernism arose in the second half of the twentieth century. The term is used to describe the era of change in the prevailing attitude and culture that the Church finds itself in. Understanding postmodernism and its implications, and responding correctly to them, is vital for the Church of the 21st century.

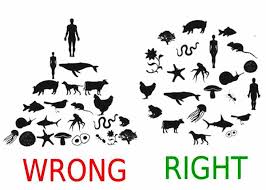

Postmodernism seeks to discredit religious faith as truth and insists that "there is no single truth". It undermines the certainty of science and other belief structures. Postmodern values include the rejection of hierarchy, suspicion of institutions and strong emphasis on personal choice as the final arbiter. It is also against dogmatism and legalism.

What is really right?

What is really right?

The idea of "objective truth" means that truth is independent of individual or cultural belief. When something is objectively true (like the existence of the moon), it is true for everyone regardless of whether they acknowledge it or not. Objectivity assumes we all live in one reality, even though we may experience it differently or have different beliefs about it. Those who believe in objective truth have a common base from which to discuss what is true and what is not, because we all live in the same real world. Postmodernists deny this shared reality. Instead, they claim that different cultural groups live in different realities; that a people's reality is their perception or interpretation of the external world, but not the world itself.

Postmodernists believe that ideas such as values and morality are socially and culturally constructed and that if we seek to interpret truth we are attempting to create something that does not exist. They believe "a thing is true because I believe it", there are no moral obligations.

According to the postmodern worldview, modernism and the Western world society are out of date. "Truth" is relative; what constitutes truth is up to each person to determine for him/herself. Postmodernists are typically atheistic or agnostic while some prefer to follow eastern religion thoughts and practices. Many are naturalists in outlook including humanitarians, environmentalists, and philosophers. They challenge core religious and capitalist values of the West and seek change for a new age of liberty within a global community. Many prefer to live under a global, non-political government without tribal or national boundaries and one that is sensitive to the socioeconomic equality of all people.

Postmodernism is sceptical of explanations that claim to be valid for all groups, cultures, traditions, or races, and instead focuses on the judgements of each person. In postmodern understanding, interpretation is everything; reality only comes into being through our interpretations of what the world means to us individually.

How does this fit social structure? Some postmodernists prefer majoritarianism, ie the opinion of the majority is the only obligation, however such a notion is inconsistent because it contains a premise that should be accepted.

Ironically, postmodernism attempts to get us to think in a certain way - as any metanarrative does. It is a faith system, like atheism. Postmodernism has been absorbed into thinking around literature, art, philosophy, architecture, fiction, and cultural and literary criticism, among others.

Jesus was sent to "testify to the truth" (John 18:37). Postmodernism affirms no truth, yet its position is self-defeating - it seeks to affirm at least one absolute truth: that no truth should be affirmed. Get it?? Christianity claims to be absolutely true. As Christians, we accept the reality of both subjective and objective truth, and we believe we can discover both through a combination of our own God-given reason and divine revelation.

The Bible teaches that we can come to know a love that transcends knowledge (Ephesians 3:19), and that our relationship with God goes beyond mere statements of fact about Him. This is subjective or experiential truth. But the reality of subjective or experiential truth in no way rules out the reality of objective truth.

The Christian community must offer authenticity to the postmodern who craves it. We must consistently apply a world view based on acceptance of God's revealed Word, an authority over and above human reasoning, to all matters of life, faith and relationships.

A Creedal World View

"I Believe in God the Father Almighty, Maker of Heaven and Earth."

Arguably the most popular Christian song in 2014 was "The Creed" (Ben Fielding and Matt Crocker, Hillsong, Australia). "I believe in God the Father. I believe in Christ the Son. I believe in the Holy Spirit. Our God is three in one".

Why this talk about "creed"? What does it have to do with us, in the modern 21st century?

The term "Creed" sounds like ecclesiastical mumbo jumbo, a hang-over from a bygone era of men in top hats, women with long gloves and hats, a high church tradition associated with esoteric rituals. "Who cares about such things? We are progressive?!"

If "creed" is still relevant what does it mean? How can we apply it in our lives? In our sceptical, secular, postmodern age where belief is considered personal and no absolutes exist, where anything goes, and young people reject blueprintism, we want a menu of choices.

Every time we click onto Facebook we are confronted by a new string of messages, with surveys and quizzes that want to tell us who we are, what we are really like, what lies in future, what we ought to believe in. It is good to be open, but we still need anchors, reference points, so that we are not aimlessly adrift.

What should we believe? A creedal world view gives us clues, and provides a useful backdrop for considering world views such as liberalism and postmodernism.

Reimagining the early Church

Try to imagine what it must have been like for fourth century Christians.

The early church had almost nothing external that we take for granted. No New Testament (till the mid-300s), no "100 versions of the Bible on a single ap", no denominations, buildings, or programs like we have today, no Bible Colleges or Alpha course, few books. Theologians and church leaders were frequently picked up off the street, tortured and killed, with state approval and by popular demand. From one end of the Empire to the other most cultures were multi-religious, polytheistic, worshipping a pantheon of gods, believing in an array of myths and superstitions. Christianity did not become the official religion until 380. Cities and towns, markets and stadiums were littered with temples and shrines of ancient gods; it was not possible to walk down the street without encountering the sites, smells and rituals of religion. Every home had household gods (where TVs are placed today). Each morning Junius and Julius would pay their respects to the family gods before going to school. Mrs Andronicus would go to the priest or soothsayer before going to agora to shop: what's the weather forecast for today? what portents are in the heavens?", to be on the safe side.

Religion was everywhere, invasive, and constricting, it bound up lives ("religio", or "relegare" meant "to bind, or tie up"). "Faith" was a constant competition, like some "European Idol". "My gods are better than your gods because we win more battles, our crops are better." Those who were not polytheistic were regarded with suspicion: "You have no gods? You must be an atheist." And everyone knew that atheists were the root cause of problems, because they upset the gods and the entire community suffered as a result. Justin Martyr's defence before being executed in 167 was that there was only one God, so he died for allegedly being an atheist. Monotheists were persecuted.

After the conversion of Constantine in 312, it progressively became fashionable (but not yet legally obligatory) to retire the old gods and follow monotheistic Christianity; this downtrodden "foreign religion" now became politically correct, adopted by the rich, educated, powerful and beautiful people. Yet uncertainty remained, "What do we believe? What if we get it wrong?"

Controversies raged about points of doctrines and church politics. So, in 325, Constantine gathered as many church leaders as he could, in Nicea (not far from modern Istanbul, in Turkey), locked the door, and told them not to come out until they agreed on a basic platform for Christian belief. What they decided and codified, for the very first time, was what we refer to as the Nicene Creed.

Why write out a Creed? The more people became Christians, as their numbers grew, right across the Empire, local variations gave rise to serious disagreement. Was Jesus God, or a man? Did the Holy Spirit come from the Father, or the Son? According to Tertullian (died 220), there was one God, made up of three persons (Father, Son and Holy Spirit), a tri-unity, or "Trinity".

That was sometimes confusing and contentious. In some parts of empire Christians were being fed to lions, in others they were lionised. There was no "Bible" as such, Gentile believers did not understand the Jewish Torah; few could read, letters the apostles and church fathers wrote (those that existed) were copied out laboriously and read in public meetings; most people listened rather than read; it is the same today in some parts of the world. The way to retain a core set of a single beliefs was to memorize those beliefs, then repeat them. That is why the early church leaders found themselves locked in and not let out until they came up with a cogent statement of beliefs that all Christians could sign onto, at the risk of becoming mechanical repetition.

Believing in God the Creator and Father as the basis for a world view

The Nicene Creed begins with "I believe in God". So what! Everyone believed in God, the more gods the better. Second-hand gods were a Sesterius a dozen at antique shops. What made the Christian God different? Christians taught that the One they worshipped was not just "any old god", but the One True God, the only one.

That was revolutionary. Only one, the Maker of everything; without whom we would not exist. He was the One who made everything. That was better than atheism (belief in no god), but no more than what the Deists believed. Or those who (even today) claim to believe in Him, bow to Him several times a day but use that as a cloak for committing evil atrocities in his name (witness the news broadcasts every day). There are two great tragedies in our century: (i) the fact that many people no longer believe in God; (ii) that many who do believe in God do so fanatically, lethally, in the wrong way. It is not enough just to believe in God.

The writers of the creed qualified their statement by adding that God was "Father". God sent His son into the world to bring us into His family. That was revolutionary, it changed every relationship they had, the way they approached the great questions about life and eternity. "One God", no other; active in the world, but personally involved in our lives. Not stuck in a temple, when the lamps were extinguished at the end of the day. Not just concentrating on getting the next harvest in for His devotees, averting plague, ensuring fertility, or giving them victory over other tribes. The God of the Christians went with them on the job in the copper mine; to the busy agora; when they walked the dusty roads to the next village; and when they set out on the ancient trade routes to do business.

Christians believed that God was father, He was ever-present; His address was their address. He was there when little Junius and Julius and Mrs Andronicus sat down with the rest of the family at the dinner table; He was with them at all times.

This declaration changed God from being an idol on a shelf, who would capriciously punish them if they forgot to light a votive candle, into One who was real, transcendent, supreme over all religions and gods (who were not really gods anyway). It changed their attitudes towards one another; Aldi the slave from Germanica was no longer a chattel who was worth as little as a pot of olive oil or a goat, but a child of God, a member of God's family, a brother even. It was revolutionary, because it gave them hope. However, it was dangerous, as it threatened the status quo, it challenged the accepted and respected social order.

The Christian religion was not just another faith; it implied overthrowing all other gods, religions, traditions, philosophies, all world views but its own. God was real, not just a dumb image of gold, wood, or stone, but a Heavenly Father.

The Christian world view is expressed in the words of Augustine of Hippo, "You have made us for yourself, and our hearts are restless until they find themselves in you".

The writers of the creed went one step further. They declared that the God of the Christians was the "Maker of Heaven and Earth". He was creator of everything, in heaven and earth, thereby addressing the dualistic teaching of the Gnostics, who believed that Almighty God would never touch the physical realm. The Christian world view taught that God the creator became flesh, came to earth, physically, in the person of His Son (Hebrews 1:1-3). He was misunderstood, rejected, crucified, but rose again, and gives the authority to those who believe in Him to become children of God themselves (John 1:11-12). To cap it all off, God sent His Spirit to earth, to take charge and give power and authority to His followers; these followers turned the world upside down.

Today, hundreds of millions believe in God, as Almighty, Creator, sustainer, but unapproachable, impossible to please, one who predestines our lives and destinies, all powerful, like some Big Controller. They acknowledge that we live, breathe, and have our being because of Him (Acts 17:28); but He is distant.

Creed as a world view

A clearly defined Christian world view changes all that. "I believe in God who is Almighty, Creator, Maker of Heaven and Earth" who brought everything out of nothing, now our Father through Christ. As Creator He makes us new, give us a brand new start. We live because He lives. As Father, welcome us into His family, into His presence; and gives us confidence. He is always standing by, ready to help. He is interested in the detail of our lives, the issues we face, and wants us to be with Him forever. So the declaration goes from "we believe" to "I believe". That changes our world view, our perspective, totally. It gives us meaning, hope and freedom. Sometimes we need to put it into words, say it out aloud. Christians in the fourth century who memorised the creed affirmed it when they took the shopping bag down to the agora, when they took their children to Scolasticus the teacher, when they wrapped their togas tight against the cold wind; and when they met others who were saying the same thing it gave them a strong basis for relationship, just like a family.

A creed (or catechism), can be an empty recitation, or a heartfelt declaration. Understood and applied to the individual life, and to history, such a Christian world view can work powerfully today. Unlike Liberalism and Postmodernism, the Christian creedal worldview puts a living Christ at the centre, as one who gives us a real and reliable confidence in this world, and hope for the next.

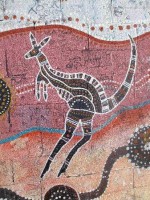

What About Indigenous Cultures in Australia?

According to a Western interpretations of history, England's Captain James Cook "discovered" the east coast of Australia in 1770. The First Fleet arrived from England in 1788 and created a penal settlement (one of several that would be established in the continent) following the loss of the American colonies. Over time, political doctrines supporting settlement and what attempted genocide would centre on assumptions that:

- the land was uninhabited (terra nullius, in spite of documentary evidence to the contrary, dating back to Cook's own diary) at the time of settlement; this belief made it easy for some legislators to determine that indigenous Australians were merely "fauna"; it also set the scene for the break-up on ancient clans and families

- the first Australians (who were nomadic) did not have an "attachment" to the land because they did not recognise or practise land ownership in the way Europeans did (eg fences and title deeds); therefore, ownership of the land was up for grabs and management under English/colonial law

- the Aboriginal races (of which there were scores, possibly hundreds) would eventually "die out" (it was asserted that the European settlers had a responsibility to "smooth their dying pillows"; in parts of the continent there were concerted efforts to hasten this process, including by poisoning)

- Aboriginal Australians did not have religious systems - there was, after all, no evidence, eg idols (compared with indigenous groups elsewhere in Oceania, such as New Guinea and New Zealand). It is now clear that Aboriginals throughout Australia, and Torres Strait Islanders, were deeply religious.

Aboriginal myths centre on beings who created the land, people, plants and animal life at the beginning of time, the Dreamtime. Rather than praying to a god, each group believes in ancestral beings, whose images are often depicted in tangible forms, such as rock art. Landscape features (mountains, rivers, and so on) may be seen as embodiments of these beings, or believed to be the result of something that occurred during the Creation Period, such as a river having formed when the Rainbow Serpent passed through the area, or a depression in a rock representing the footprint or sitting place of an Ancestral Being. Each tribe had its own ancestral beings, with an overlap of beliefs. Aboriginal people often interpret dreams as memories of events during the Creation Period.

Ceremonies play an important part in Aboriginal life, eg when a boy becomes a man, or in order to ensure a supply of plant and animal foods, or story telling intended to pass on oral traditions. These ceremonies take the form of bodily decoration, ceremonial objects, chanting, singing, dancing or rituals. Totemic associations with animals are elaborate and ritualised. Custom is very important. Some songs are stories connected to the Ancestral Beings are told and retold, some being "open" for women and children to see and hear; others are restricted or "secret-sacred", only for the initiates to learn. Kinship systems, obligations and privileges are complex. Aboriginal burial practices vary and it is common for Aboriginal people not to speak of the dead by name.

Early attempts to reach Aboriginal communities with the Christian message ran into obstacles. They seemed to have little in common with Western culture. In parts of Australia Christianity was associated with mission schools and family break-up. The Christian community was slow to respond to injustice, prejudice and organised genocide. The experiences of Aboriginal Australians over the past 100 years have been complex and tragic; the legacy continues. The idea of "reconciliation" has been politicised or turned into a cliche. The "spiritual attachment" many Aborigines feel to the land has been misunderstood in evangelical circles. Everyone has felt spiritual needs. Only Christ can meet those needs. The Christian church needs to take to a lead in genuine reconciliation.

A sound Christian world view to approaching any indigenous culture is paramount. Sharing the Gospel with Aboriginal people begins by focusing on the Good News about His creation, His teaching and His promise of freedom. Christ is greater than the spirit world. Reconciliation with God, forgiveness, and peace with others come through Christ and the cross. It is not formulaic. Genuine Christian life is not individualistic, rather, it involves the community, looking after the poor, the alienated, widows, orphans and neighbours, sharing with those in need, and ministering to spiritual needs with the help and wisdom of the Holy Spirit. Jesus Christ would be "at home" sitting beside a camp fire with His Aboriginal friends and neighbours, sharing love and hope for eternity in a traditional community. This is a challenge for all of us who follow Him to have the same perspective.

Indigenous Spirituality

"Aboriginal spirituality is defined as at the core of Aboriginal being, their very identity. It gives meaning to all aspects of life including relationships with one another and the environment. All objects are living and share the same soul and spirit as Aboriginals. There is a kinship with the environment. Aboriginal spirituality can be expressed visually, musically and ceremonially." (Grant, 2004)

Part of the Australians Together journey of listening, learning and living in respectful relationship with one another involves seeking to understand Indigenous spirituality, which is fundamental to many Indigenous people's identity and worldview.

Someone with extensive knowledge of this topic is Indigenous elder, Graham Paulson. Graham is the first ordained Indigenous Baptist pastor in Australia, and now has over 50 years of ministry experience in remote, rural and urban contexts. Drawing on his experience and his deep knowledge of Indigenous Australian cultures, Graham Paulson explains several core aspects of Indigenous spirituality.

1. Aboriginal Spirituality is Animistic

In an animistic world everything is interconnected, people, plants and animals, landforms and celestial bodies are part of a larger reality. In this world, nothing is inanimate, everything is alive; animals, plants, and natural forces, all are energised by a spirit. As such, humans are on an equal footing with nature; are part of nature and are morally obligated to treat animals, plants and landforms with respect. In this world, the invisible and the visible pulse with the same life and the sacred is not separated from the secular, they are interconnected and interactive.

In this world, the unseen spiritual forces are stronger and hold sway over all nature. A respect for the power of spirit forces is learned from early childhood, particularly in relation to religious or social taboos. These spiritual forces are believed to have power to make rain, foster natural growth, assist in hunting and food gathering and even to the finding of spouses or partners. It is believed that they have the power to act against the wishes of people if the correct ceremonies and/or rituals are not practised or observed. It is believed that crossing the boundaries of social taboos will incur their wrath.

2. Aboriginal Spirituality is a Cosmogony

Cosmogony is a theory or story of the origin of the universe. Aboriginal cosmogony begins at the 'Dreamtime'. This is the time before the world was shaped the way we know it to be now. Hidden in the sky, in the sea and under the surface of the earth are dreamtime heroes, also called creation ancestors, who are part human, in terms of their emotions and intellect, part animal bird or reptile, in terms of their physical shape, and part super-human in terms of their power and their creative ability. At some point in the dreaming they emerged from their hidden worlds and as a result of their actions and inter-actions they shaped the world as we have it today.

3. Aboriginal Spirituality is Earthly

Vicki Grieves (2009) explains: "These ancestors created order out of chaos, form out of formlessness, life out of lifelessness, and, as they did so, they established the ways in which all things should live in interconnectedness so as to maintain order and sustainability. The creation ancestors thus laid down not only the foundations of all life, but also what people had to do to maintain their part of this interdependence - the Law.

The Law ensures that each person knows his or her connectedness and responsibilities for other people (their kin), for country (including watercourses, landforms, the species and the universe), and for their ongoing relationship with the ancestor spirits themselves."

4. Aboriginal Spirituality is Totemic

A totem is a natural object, plant or animal that is inherited by members of a clan or family as their spiritual emblem. Totems define peoples' roles and responsibilities, and their relationships with each other and creation. Totems are believed to be the descendants of the Dreamtime heroes, or totemic beings.

Dreamtime heroes are linked to space and place. The places from which they emerged and travelled, and inter-acted with other spirit-beings, all become associated with the particular hero or heroes and are valued according to the importance of that part of creation to the local tribal group.

Each clan family belonging to the group is responsible for the stewardship of their totem: the flora and fauna of their area as well as the stewardship of the sacred sites attached to their area. This stewardship consists not only of the management of the physical resources ensuring that they are not plundered to the point of extinction, but also the spiritual management of all the ceremonies necessary to ensure adequate rain and food resources at the change of each season.

A typical boy's story might begin before he is even born. As his mother becomes conscious of his first movement in the womb she immediately has to take note of the area so that the infant will become identified with the spirit of the particular area in which she is located. This is based on the belief that the spirit of that area has energised the infant in the womb and the child becomes inextricably linked with the spirit associated with the dominant creation of that place, as his conception totem.

5. Aboriginal Spirituality is Oral

At the point of birth the child has allocated to him the appropriate birth totem. He automatically receives a skin totem and a clan totem. His spiritual responsibility in life will be to learn the songs and dances, and how to perform the ceremonies, that are associated with those totems so as to energise the relevant spirit within those parts of creation. As each clan family walks their country the law of averages ensures that different people become associated with different parts and the whole area will ultimately be cared for.

6. Aboriginal Spirituality is Hierarchical

This aspect of Aboriginality is not very well understood by many people in traditional communities today let alone urban communities. The gaining of power by the acquiring of traditional and ceremonial knowledge is an experience only reserved for the initiated whose personality and character satisfy their traditional elders.

http://www.australianstogether.org.au/stories/detail/indigenous-spirituality

What is really right?

What is really right?